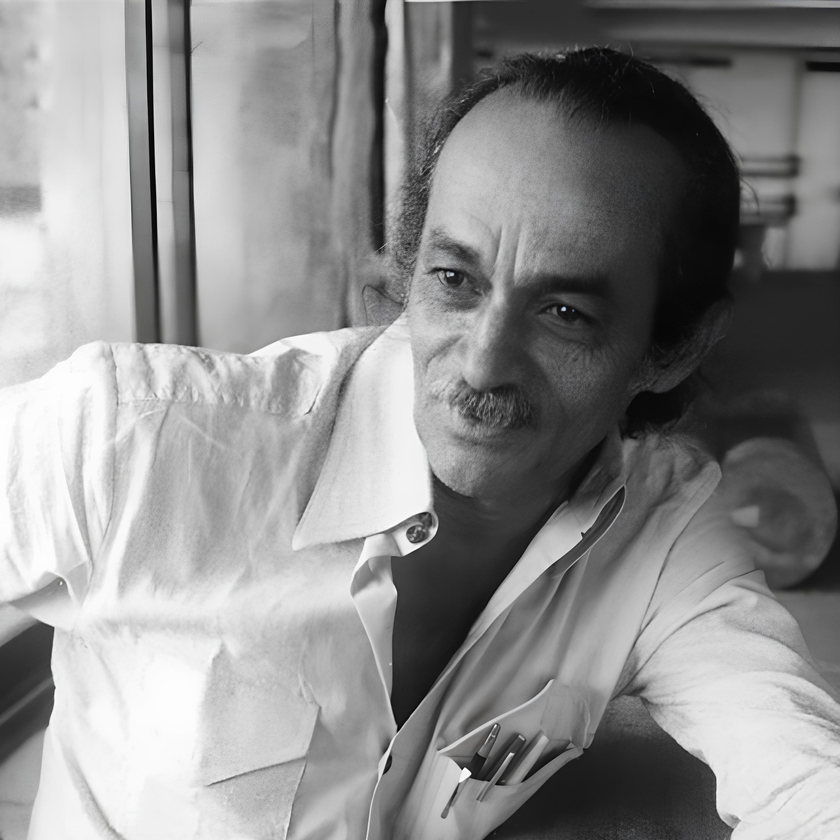

José Zanine Caldas

José Zanine Caldas (1919–2001) was a pioneer of Brazilian design and architecture, one of the creators of modern material culture in Brazil. His varied legacy in architecture, design and art is still the subject of study. In 1989, the Parisian Museum of Decorative Arts dedicated a retrospective exhibition “Zanine — Architect and Forest” to him, and the French Academy of Architecture awarded him a medal. His work is on display in museums around the world.

He was known for creating architectural models, industrial furniture and handcrafted items. His practice included sculpture, landscape design, social architecture and luxury villa projects, and research into the use and reuse of Brazilian wood. The ecological approach became his guiding principle and ensured an inextricable link between aesthetics and ethics.

Caldas' aesthetics are based on a dialogue with folk crafts and building practices. He had no academic background and was self-taught in many disciplines. For more than 10 years, he ran a workshop specializing in large-scale architectural models, where he designed more than 500 models for leading Brazilian architects, including Oscar Niemeyer and Lucio Costa.

In the 1970s he moved to the coastal town of Nova Viçosa. The thoughtless cutting down of precious forests that took place in the area inspired him to create a collection, later called Móveis Denúncia — Protest Furniture. The movement began with experiments in using leftover wood from logging. He only used fallen or dead trees.

Caldas has always turned to local artisans to highlight the beauty of the region's natural resources. His monumental objects were often made of solid wood.

The designer sought to highlight the rare and precious skills of artisans by often working in collaboration with craftsmen in carving and canoe building. His friend, sculptor Frans Krajcberg, helped him to achieve more expressive forms. These pieces always remain as close as possible to the original nature of the wood, retain the texture and color of the original material, imperfections such as knots or cracks and combine surprising brutalism and sensuality. In his search for an original language, Caldas also preserved the visual codes of modernism, introducing them into the atmosphere of homes, offices and public spaces. He is one of the most important creators of a distinctive Latin American design vocabulary.

In the 1970s José Zanine Caldas returned to Bahia in eastern Brazil and began a new series. Titled Protest Furniture / Móveis Denúncia, it directly confronted the destruction of the Atlantic coastal rainforests. Caldas created pieces from “found trees” — solid fragments of wood left behind after deforestation. Through their monumental scale, he sought to reveal the true diameter of the trunks and to preserve the memory of Brazilian trees for future generations.

Another source of inspiration came from the craft of canoe building. Industrialisation and the construction of highways had transformed the landscape, leaving artisans without commissions. Caldas invited them to redirect their expertise — to apply their intimate knowledge of wood to the art of furniture making. Their collaboration stood in stark contrast to the impersonal logic of mechanical labour: in it, creativity and the unique skills were placed at the forefront. The visionary project was deeply rooted in the local context and the history of the place. Beyond furniture production, it also initiated social change. The establishment of the Móveis Denúncia workshop led to the creation of a crafts school in Nova Viçosa — a space where residents could share knowledge, and where inventiveness and creativity were actively nurtured.

Caldas’s pieces — sensual, powerful, uncompromising — were always conceived to reveal the potential and inherent beauty of each fragment of wood. Some remained one of a kind, while others could be reproduced in several versions. After crafting a 1:10 scale model, he would hand it over to the workshop, where artisans used their knowledge to bring it to life. This careful mode of production helped revive and safeguard traditional skills, and techniques. This experience transformed the life of a region and fostered a culture of making that continues to this day in Bahia, thanks to José Zanine Caldas.

Read more